The Front Surface of the Eye continuous With a is the

Eye

- Index to image pages

- Overview / basic layers

- Basic layers: sclera, choroid, retina

- Anterior and posterior chambers

- Specific structures

- Cornea

- corneal transparency

- Iris

- Ciliary body

- Suspensory fibers

- Ciliary processes

- Aqueous humor

- Canal of Schlemm

- Lens

- Retina

- Layers

- Cells of the retina

- Comparison of central and peripheral retina

- Blind spot

- Pigmented epithelium

- Embryology

- Embryonic head, with brain vesicles and optic cups

- Embryonic optic cup and lens vesicle

- Optic nerve

- Vitreous humor

- Eyelid

- Conjunctiva

SAQ -- Self Assessment Questions

Overview / Basic structure of the eyeball

Overview / Basic structure of the eyeball

The eyeball consists of three principal layers.

- The outer layer, or sclera, consists of dense fibrous connective tissue.

- The sclera is the "white" of the eye.

- The sclera is continuous with the transparent substantia propria of the cornea.

- The exposed front surface of the eye, including the cornea, is also covered by a thin, non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium.

- The next layer, or choroid, consists of heavily pigmented loose connective tissue, including many melanocytes.

- The choroid is normally not visible behind the "white" of the sclera.

-

The choroid is continuous with the iris; together the choroid and iris are called the uvea.

The choroid is continuous with the iris; together the choroid and iris are called the uvea. - A hole in this layer, the pupil, allows light to pass through.

- The inner layer, or retina, includes two portions.

- The neural retina is the photoreceptive, imaging-processing tissue.

- The pigmented epithelium lies behind the neural retina; it also extends forward to line the hidden side of the iris.

- The lens is a specialized epithelial structure, suspended behind the pupil.

- The anterior chamber, a space filled with aqueous humor, lies between the iris and the cornea.

- The posterior chamber lies behind the iris.

TOP OF PAGE

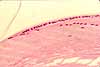

Cornea

Cornea

The cornea consists of a thin surface epithelium (non-keratinized stratified squamous) overlying a layer of dense fibrous connective tissue, called substantia propria.

Although the corneal tissues are made of the same tissue elements as other body parts (i.e., epithelial cells, collagen, fibroblasts, etc.), the cornea is quite unlike most tissues in that it is perfectly transparent.

Compare and contrast the tissue layers of the cornea with those of other body surfaces:

The features which distinguish corneal tissues from those of other body surfaces are all related to its transparency.

The epithelium of the cornea is continuous with the epithelium of the conjunctive, both that of the eyeball itself and that of the inside of the eyelid, which in turn is continuous with the epidermis of skin on the exposed surface of the eyelid.

The epithelium of the cornea is continuous with the epithelium of the conjunctive, both that of the eyeball itself and that of the inside of the eyelid, which in turn is continuous with the epidermis of skin on the exposed surface of the eyelid.

Corneal epithelium is very thin (only a few cells thick).

Notably (i.e., unlike most other stratified squamous epithelial tissue), corneal epithelium lies flat against the underlying substantia propria. Compare with skin, where the basal surface of the epidermis is indented by many dermal papillae. (Dermal papillae presumably help reinforce epithelial attachment against mechanical stress, a function which is hardly necessary for the cornea.)

The exceptionally thick basement membrane between corneal epithelium and substantia propria is called Bowman's membrane (named after William Bowman, b. 1816; this is the same Bowman who gives his name to Bowman's capsule of the renal glomerulus).,

Like most dense fibrous connective tissue, the substantia propria of the cornea is mostly collagen and ground substance, with fibroblasts as the most common cell type. Quite unlike most other dense, fibrous connective tissue, the corneal connective tissue is perfectly transparent.

Collagen of the cornea is organized into extremely regular layers. All the collagen fibers in one layer are arranged in parallel, and alternating layers run in different directions.

Corneal connective tissue has no blood vessels. (You don't need a microscope to confirm this; just look in a mirror.)

Even though cells of the cornea are not very active metabolically, they still need oxygen and nutrients. As long as the cornea is in direct contact with air, oxygen can be absorbed directly. Nutrients can diffuse into cornea from aqueous humor.

Cells of corneal connective tissue are limited to fibroblasts. There is no immune-system component, hence the relative ease with which corneal tissue can be transplanted without need for careful tissue typing.

At the inner surface of the cornea, a thick basal lamina (Descemet's membrane, named after Jean Descemet, b. 1732) separates the substantia propria from a cellular layer, resembling a simple low cuboidal epithelium, called corneal endothelium. (This is a unique use of the term endothelium; it is not related to vascular endothelium.) It is believed that this corneal endothelium is essential for maintaining corneal transparency, by regulating the composition of ground substance in the substantial propria.

Clinical note:The surgical procedure of endothelial keratoplasty replaces with a transplant both corneal endothelium and Descemet's membrane, to address Fuch's dystrophy.

Corneal epithelium contains free nerve endings. Since pain seems to be the only sensory modality that functions for corneal tissue, biologists long ago decided that free nerve endings elsewhere may also represent pain fibers.

TOP OF PAGE

Corneal transparency.

The tissue elements of the cornea are specialized for transparency. The effectiveness of this design can be readily seen by looking in the mirror and comparing cornea with sclera (the white of the eye). However, apart from the cornea's obvious absence of blood vessels, its tissue composition appears almost identical to that of the sclera. Yet unlike the sclera, the cornea is marvellously transparent.

For a fairly recent, detailed review of mechanisms underlying corneal transparency, see Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, Vol. 49, pp. 1-16 (November 2015).

Below is a simplified introduction:

The transparency of the cornea is based primarily on the regularity of its tissue components, which minimizes the number of surfaces where light can be refracted or reflected.

At the limbus (the edge of the cornea, where the cornea meets the sclera), it is apparent that the epithelium of the sclera is almost identical to that of the cornea, except for a slightly less regular basal layer. Similarly, collagen of the corneal substantia propria is not noticably different from collagen of the sclera, except for being slightly more uniform in arrangement. But these small differences are significant. The cornea is transparent while the sclera is opaque. The effect is rather like the difference between packed snow and crystalline ice -- both have the same composition (frozen water), but one is opaque (by scattering the light off the surfaces of many tiny snow crystals) while the other is crystal clear.

Although most cells and fibers are colorless, the surfaces of these elements can scatter light when irregularly arranged. Similarly, light scattered from colorless and transparent ice crystals produce the familiar whiteness of winter snow. Such scattering (together with absorption of light by pigments such as melanin and hemoglobin) prevents light from passing freely through most tissues.

Features of the cornea which minimize the scattering of light include the following:

- Both outer and inner surfaces of the corneal epithelium are smooth.

- The collagen fibers of the substantia propria are arranged into uniform layers with parallel fibers within each layer (unlike the more irregular texture of collagen in the sclera and in the dermis of the skin).

- The water content of the ground substance is carefully regulated, to maintain uniform spacing among collagen fibers.

Collagen fibers are formed extracellularly, self-assembling from tropocollagen molecules (secreted as procollagen by fibroblasts). The regulatory machinery responsible for the regular arrangement of collagen fibers in the cornea remains unknown.

The low cuboidal cells which form the cornea's innermost layer, the so-called corneal endothelium, actively pump ions and water from the corneal ground substance into the aqueous humor, to prevent excess water from disturbing the regularity of the collagen layers and causing opacity.

TOP OF PAGE

Iris

Iris

Functionally, the iris is a rather simple opaque ring surrounding and controlling the diameter of its central aperture, the pupil.

However, the iris does have some peculiar histological features.

- The iris is the only internal organ which is clearly visible from outside the body. The visible surface of the iris consists of loose connective tissue and includes blood vessels.

- The color of the iris ("eye color") results both from scattering of light by its trabecular meshwork of collagen fibers and from absorption of light by melanin granules in scattered melanocytes.

- Variation in eye color result from individual differences in the distribution and density of melanocytes and trabecular meshwork.

- The posterior (hidden) surface of the iris is an intensely pigmented extension of the embryological optic cup (the same structure which forms the retina and the pigmented epithelium). This tissue continues as the ciliary processes around the perimeter of the iris.

- A ring of smooth muscle surrounding the pupil comprises the pupillary sphincter.

- The pupillary dilator is not ordinary smooth muscle but rather contractile extensions of myoepithelial cells of the deep layer of the two-layered pigmented epithelial tissue that comprises the posterior surface of the iris.

TOP OF PAGE

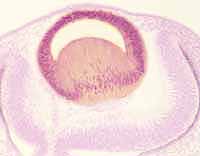

Lens

Histologically, the lens is bizarre. It is an isolated island of epithelial tissue with an anterior layer that is simple cuboidal and a posterior layer consisting of extravagantly elongated cells, called lens fibers, that are packed with lens protein.

This pattern is most readily understood by considering the embryology of the eye. The lens forms as a vesicle that pinches in from surface ectoderm.

This pattern is most readily understood by considering the embryology of the eye. The lens forms as a vesicle that pinches in from surface ectoderm.  In basic plan, it is therefore a "bubble" of epithelial tissue. The cells on the posterior of this bubble then grow incredibly long until they extend across almost the entire thickness of the lens, save only a thin layer of cuboidal epithelium that remains on the lens' anterior surface.

In basic plan, it is therefore a "bubble" of epithelial tissue. The cells on the posterior of this bubble then grow incredibly long until they extend across almost the entire thickness of the lens, save only a thin layer of cuboidal epithelium that remains on the lens' anterior surface.

At the edge of the lens, one can see where these two different epithelial cell shapes meet one another.

The shape of the lens (and hence its focal length) is determined by tension exerted through the suspensory fibers, controlled by smooth muscle of the ciliary body.

The shape of the lens (and hence its focal length) is determined by tension exerted through the suspensory fibers, controlled by smooth muscle of the ciliary body.

TOP OF PAGE

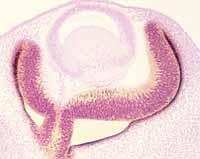

Ciliary body and suspensory fibers (zonules)

Deep to the limbus (i.e., the cite where the cornea meets the sclera), the choroid layer is thickened into the ciliary body.

Deep to the limbus (i.e., the cite where the cornea meets the sclera), the choroid layer is thickened into the ciliary body.

- The ciliary body is a ring of smooth muscle fibers arranged concentrically around the opening in which the lens is suspended.

- The lens is suspended from the ciliary body by thin fibers of collagen, called suspensory fibers or zonules.

Together, the ciliary body and suspensory fibers control the shape of the lens.

Together, the ciliary body and suspensory fibers control the shape of the lens.

- When smooth muscle of the ciliary body is in a relaxed state, the elasticity of the eyeball (sclera) puts tension on the suspensory fibers, which in turn stretches the lens radially, thereby making it thinner. In this condition, the lens brings distant objects into focus on the retina.

- When smooth muscle of the ciliary body contracts, the opening in which the lens is suspended becomes (slightly) smaller and tension on the suspensory fibers is relaxed. The lens is then allowed to adopt its "resting" shape, which is more round. In this condition, the lens brings nearby objects into focus on the retina.

- Note that a stretched lens, for distant focus, is maintained by a relaxed muscle. Hence eyes at rest are focussed for distance vision.

- Conversely, a contracted muscle is responsible for a relaxed lens, for near focus. Close work is tiring because the ciliary body must remain in contraction to maintain focus.

Ciliary processes and aqueous humor

Ciliary processes and aqueous humor

The surface of the ciliary body is covered by an extension of the embryonic optic cup (the same tissue which forms the retina and the pigmented epithelium). Small projections of this tissue form the ciliary processes. The epithelium of the ciliary processes secretes the aqueous humor.

Aqueous humor flows from its site of formation in the posterior chamber (i.e., behind the iris) through the pupil into the anterior chamber. From there it drains into the canal of Schlemm and hence into venous drainage.

This is one of three sites associated with the nervous system where a special fluid is produced by a unique tissue, with this fluid needing an outlet elsewhere to avoid buildup of pressure. The other two are the endolymph of the ear, produced by stria vascularis and drained through the endolymphatic sac; and cerebrospinal fluid of the brain, produced by choroid plexus and drained through arachnoid villi into the superior sagittal sinus. In each of these sites, an imbalance between production and drainage can cause neurological symptoms.

Clinical note: An imbalance between the formation and drainage of aqueous humor can create increased pressure. Increased fluid pressure inside the eyeball reduces blood flow into the eyeball, leading to glaucoma.

Canal of Schlemm

Canal of Schlemm

The canal of Schlemm, also called the scleral venous sinus, is a network of connective tissue spaces at the edge (limbus) of the cornea through which aqueous humor can escape from the anterior chamber. From here the fluid seeps into venous drainage. (The traditional name "canal of Schlemm" commemorates Friedrich Schlemm, b. 1795.)

TOP OF PAGE

Retina

The retina consists of two fundamentally distinct layers, the neural retina (often called simply "the retina") and the pigmented epithelium. These two layers derive, respectively, from the front and back ectodermal surfaces of the embryonic optic cup.

The neural retina is the light-sensitive tissue of the eye.

The neural retina is the light-sensitive tissue of the eye.

The retina is famously built "upside down." That is, the photoreceptor cells (rods and cones) are located in the back of the retina, so light must pass through all of the layers of the neural retina before getting to the receptors.

Even worse, the blood vessels which serve the retina are spread across the front surface, so light on its way to the receptors must also pass by the blood vessels. (Evidently, our visual system is designed to ignore the blood vessels; otherwise every view of the world would have a superimposed array of branching blood vessels and coursing red blood cells.)

As one final insult, the nerve fibers which eventually travel from the eye through the optic nerve must pass through the layers of the retina, leaving a "blind spot" where they do so. (And once again, our visual system is designed to ignore the blind spot, filling in the corresponding "hole" in the visual field with whatever color and texture does the best job of hiding the blind spot.)

The fovea is a central patch of retina with high acuity. Here the issues noted above are minimized by thinning the layers inward from the photoreceptors, displacing cell bodies, nerve fibers, and blood vessels away from this spot.

[ How to "see" your own blind spot. ]

Cells comprising the neural retina give the appearance of several layers. (Click on the thumbnail to right to see the layers labelled.)

Cells comprising the neural retina give the appearance of several layers. (Click on the thumbnail to right to see the layers labelled.)

Historical note: Among the first to describe these layers in microscopic detail was William Bowman (b. 1816), after whom Bowman's membrane of the cornea is named.

- The innermost layer (i.e., the layer closest to the center of the eyeball) is the inner limiting membrane, a basal lamina separating nervous tissue of the retina from connective tissue of the vitreous humor.

- The layer of nerve fibers contains axons from ganglion cells which travel across the retina to the optic nerve and hence past the optic chiasm into the optic tract and into lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus.

- The ganglion cell layer contains the cell bodies of ganglion cells, the nerve cells whose axons project through the optic nerve to the thalamus.

- The inner plexiform layer contains dendrites of ganglion cells synapsing with axons of bipolar cells.

- The inner nuclear layer contains the cell bodies of bipolar cells

- The outer plexiform layer contains dendrites of bipolar cells synapsing with axons of photoreceptor cells.

- The outer nuclear layer contains the cell bodies of photoreceptor cells.

- Between the outer nuclear layer and the receptor layer is the site of the outer limiting membrane, a basal lamina bounding the neural retina. The outer segments (rods and cones) of the photoreceptor cells penetrate this outer limiting membrane to contact the pigmented epithelium.

- The receptor layer contains the photoreceptive outer segments (rods and cones) of photoreceptor cells.

The pigmented epithelium is the outermost layer of the retina, consisting of cuboidal epithelial cells derived from the outer layer of the embryonic optic cup. The dense melanin pigment of this layer absorbs light not captured by photoreceptors. The cells of the pigmented epithelium also contribute to the maintenance of photoreceptors, "recycling" membranes that are shed from rod and cone outer segments.

Clinical note: Although cells of the pigmented epithelium are intimately associated with outer segments (rods and cones) of receptor cells, this surface where the neural retina contacts the pigmented epithelium is inherently extremely fragile. This is the site where retinal detachment can occur.

Three principal cell types comprise the neural retina. Click on the thumbnail below for a diagrammatic representation of these cells.

- Photoreceptor cells come in two types, rods and cones.

For electron micrographs of these cells, see Elektronenmikroskopischer Atlas im Internet.

- The names "rod" and "cone" are descriptive of the shapes, as seen microscopically, of the outer segments of the photoreceptors.

- Each outer segment is a highly-modified cilium, with many sheet-like folds of membrane arranged in a tall stack.

- The outer segments are in intimate association with cells of the pigmented epithelium, which provide support by "recycling" membranes shed from those segments.

- Rods are sensitive to dim light and provide night vision. Rods are more numerous in the peripheral retina.

- Cones need brighter light and provide daytime color vision. Cones are more prevalent in the vicinity of the fovea.

- Three different pigments, in three different types of cones, are each optimally sensitive to a different wavelength of light.

- Three different pigments, in three different types of cones, are each optimally sensitive to a different wavelength of light.

- Bipolar cells are small neurons named for their shape, with two short processes extending away from the cell body. One process receives synapses from photoreceptors; the other process conveys signals to ganglion cells.

- Ganglion cells are the neurons whose axons travel in the optic nerve. The dendrites of ganglion cells receive synapses from bipolar cells and provide first-order analysis of the visual image.

Several additional cell types are also found in the retina (there are horizontal cells and amacrine cells, and the retinal glia are called Mueller's cells), but the three above are the most familiar.

The retina has received intensive research investigation, so a great deal of information is available about the structures and functions of its cells. For additional details, consult your print resources or search the web. (As an example of such research, the journal Nature has published a detailed 3D description of neural connections in the retina of the mouse (Helmstaedter, M. et al. Nature 500, 168-174, 2013. A video might be found here, if Nature maintains public accessiblity for this link).

TOP OF PAGE

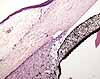

Embryology of neural retina and pigmented epithelium

The retina forms from the optic cup, which evaginates from the neuroectodermal diencephalic vesicle. The optic vesicle remains attached to developing brain; the connection between optic and diencephalic vesicles becomes the optic nerve.

The retina forms from the optic cup, which evaginates from the neuroectodermal diencephalic vesicle. The optic vesicle remains attached to developing brain; the connection between optic and diencephalic vesicles becomes the optic nerve.

The optic vesicle itself collapses into a cup. The front surface of this vesicle (the hollow of the cup) becomes the neural retina, while the back surface becomes the retina's pigmented epithelium.

Clinical note: The embryonic separation between front and back epithelia of the retina disappears as the retina develops, so that the pigmented epithelium becomes intimately associated with outer segments (rods and cones) of photoreceptor cells. However, this embryonic separation can reappear as retinal detachment if the eye is subjected to stress.

TOP OF PAGE

Optic nerve

Optic nerve

The optic nerve is properly considered a tract of the central nervous system, rather than a peripheral nerve, since the retina itself is derived from the embryonic diencephalon (i.e., from neuroectoderm). The axons in the optic nerve come from ganglion cells in the retina and project through the optic chiasm and optic tract to the lateral geniculate nucleus of the thalamus.

TOP OF PAGE

Vitreous humor

The vitreous humor is a peculiar connective tissue, essentially cell-free, fiber-free extracellular matrix, after its formation from embryonic mesenchyme.

TOP OF PAGE

Blind spot

The blind spot is the portion of the retina where the optic nerve penetrates the wall of the eyeball. Here, because there are no photoreceptors, the visual field is blank. We do not notice this blind spot because the region of the visual field which is blank for one eye is imaged by the other eye. Even with one eye closed, the blind spot is inconspicuous because our visual system seems designed to ignore it. Follow the steps below to detect the presence of a blind spot in the visual field of one of your own eyes.

- Cover or close one eye.

- With the open eye, look at a small object (preferably, one silhouetted against a fairly bland background).

- Slowly shift your gaze away from the object, turning your eye horizontally toward your nose.

- When the object is a few degrees to the side of your gaze, it should "disappear"

When an object "disappears" into the blind spot, its image has fallen onto the site where the optic nerve leaves the eye. Here it cannot be "seen" by the retina. But no matter what color the background, there is no perception of a "hole" in the visual field; the blind spot is perceptually "filled in" with background color.

And of course, when both eyes are open the area of the visual field which falls onto the blind spot of one eye is still seen by the other eye.

TOP OF PAGE

Index to image pages

- Anterior segment and limbus (overview)

- Cornea (high magnification)

- Cornea (electron micrographs from Elektronenmikroskopischer Atlas im Internet)

- Lens, iris, ciliary body (low magnification)

- Lens (high magnification)

- Iris (high magnification)

- Canal of Schlemm (high magnification)

- Ciliary body (high magnification)

- Suspensory fibers (high magnification)

- Retina and optic nerve (low magnification)

- Retina (high magnification)

- Comparison of central and peripheral retina

- Retina (electron micrographs from Elektronenmikroskopischer Atlas im Internet, mostly photoreceptor cells)

- Embryonic head, with brain vesicles and optic cups (low magnification)

- Eyelid and cornea (overview)

- Eyelid

- Conjunctiva

hamiltonlosione90.blogspot.com

Source: https://histology.siu.edu/ssb/eye.htm

0 Response to "The Front Surface of the Eye continuous With a is the"

Post a Comment